KIRK DOCKER

five pieces of (my) work worth watching

I would estimate that I have interviewed well in excess of 5000 people across my career so far. Hundreds of them stand out in my mind. Many I’ve had deep connections with, have felt their pain and have marvelled at their bravery. Others I’ve rubbed the wrong way or have found annoying, or on a couple of instances, had to embarrassingly interview again after tape was deleted or lost. I have respected all of them though. It takes courage to sit or stand in front of a camera and answer my questions, knowing that they will be broadcast to audiences of, at times, over a million people.

Over the last 15 years, my work has evolved in many ways. I’ve grown as an interviewer, learnt new techniques and changed my approach to storytelling numerous times. Despite this, the aim of my interviews always remains consistent: to show the world people who are often overlooked or misunderstood and ask them questions from a place of deep curiosity, compassion and at times playfulness, to challenge my audience to think differently about people they might judge on the surface, and then turn inwardly and hopefully reflect on their own life.

The five pieces I’ve chosen have come from close to 100 hours of finished content I’ve been involved in. They are in chronological order, starting in 2007. They are finished, so you will rarely hear my voice, but I can assure you that I have interviewed every person that speaks. Hopefully, you’ll see in these pieces a desire from me to understand. And despite at times some challenging content, I hope you will contemplate new ways of tackling those tough interactions or people you don’t understand, in your own life.

Shooting Smack, Vive Cool City, 2007

In 2007 I created a project with two friends called Vive Cool City. The idea was to shoot short documentaries about the things that interested us, that we couldn’t find answers to in mainstream media. You have to remember in 2007, YouTube didn’t exist. The only access we had to audio visual media were 5 (fairly conservative) free-to-air TV channels, and cinema and DVD releases. Online publications were non-existent.

The project was a series of mini-documentaries on topics from the fringes of life. Lots of sex and drugs exploration, unusual characters, taboo ideas like incest, urban myths and other pop culture references – “jenkem” for example, was a supposed way to get high, by collecting your own faeces, letting it ferment, then huffing the fumes. We wanted to find out whether this was true.

We hosted all our own content and broadcast on the internet via QuickTime player. We produced 3 episodes per week over three years, for a total of 301 episodes. Totally self-funded, and next to no advertising meant we had total editorial control. Our very loyal, 15 – 35 year old audience would suggest ideas and at times host stories.

The piece I’m sharing with you is our 103rd episode, Shooting Smack. We were interested in heroin addiction. In Australia at that time, heroin was either demonised via the conservative newspapers – talking of overdoses and death – or it was glamorised in programs like The Sopranos or in Martin Scorsese films – with gold syringes, that sort of thing. We didn’t feel we really understood heroin usage at all. So we had been looking for someone that would shoot-up on camera and talk about how it felt. It took us a long time to find someone, but we found PJ and his friend Eve while shooting a different story. When we realised they were both users, we asked if we could film them. They said yes. So the next thing we found ourselves buying heroin, and going back to their high-rise public housing apartment to film them. To be fair, we were nervous. We’d never been in these flats and we really weren’t sure what was going to happen – would they pass out? Overdose? Stereotypes of this situation were messing with our head.. So this is what happened, it is basically in real-time, with next to no edits.

WATCH: Shooting Smack

This story helped define the template that has become the foundation of how I interview today. It’s about being present – being in the moment, taking in what’s happening and asking questions off the back of that; being non-judgemental – leaving my assumptions and biases at the door so I could be open to learning. The truth is far different than I could have understood in my limited life experience; being curious – going in to find out, not being scared to ask dumb questions; and caring – treating all my subjects with respect and not putting my values on top of them. Finally, this is an early example of You Can’t Ask That in a way. Creating content that dispels myths. It certainly opened our eyes.

Shooting Smack, Vive Cool City, 2007

In 2007 I created a project with two friends called Vive Cool City. The idea was to shoot short documentaries about the things that interested us, that we couldn’t find answers to in mainstream media. You have to remember in 2007, YouTube didn’t exist. The only access we had to audio visual media were 5 (fairly conservative) free-to-air TV channels, and cinema and DVD releases. Online publications were non-existent.

The project was a series of mini-documentaries on topics from the fringes of life. Lots of sex and drugs exploration, unusual characters, taboo ideas like incest, urban myths and other pop culture references – “jenkem” for example, was a supposed way to get high, by collecting your own faeces, letting it ferment, then huffing the fumes. We wanted to find out whether this was true.

We hosted all our own content and broadcast on the internet via QuickTime player. We produced 3 episodes per week over three years, for a total of 301 episodes. Totally self-funded, and next to no advertising meant we had total editorial control. Our very loyal, 15 – 35 year old audience would suggest ideas and at times host stories.

The piece I’m sharing with you is our 103rd episode, Shooting Smack. We were interested in heroin addiction. In Australia at that time, heroin was either demonised via the conservative newspapers – talking of overdoses and death – or it was glamorised in programs like The Sopranos or in Martin Scorsese films – with gold syringes, that sort of thing. We didn’t feel we really understood heroin usage at all. So we had been looking for someone that would shoot-up on camera and talk about how it felt. It took us a long time to find someone, but we found PJ and his friend Eve while shooting a different story. When we realised they were both users, we asked if we could film them. They said yes. So the next thing we found ourselves buying heroin, and going back to their high-rise public housing apartment to film them. To be fair, we were nervous. We’d never been in these flats and we really weren’t sure what was going to happen – would they pass out? Overdose? Stereotypes of this situation were messing with our head.. So this is what happened, it is basically in real-time, with next to no edits.

WATCH: Shooting Smack

This story helped define the template that has become the foundation of how I interview today. It’s about being present – being in the moment, taking in what’s happening and asking questions off the back of that; being non-judgemental – leaving my assumptions and biases at the door so I could be open to learning. The truth is far different than I could have understood in my limited life experience; being curious – going in to find out, not being scared to ask dumb questions; and caring – treating all my subjects with respect and not putting my values on top of them. Finally, this is an early example of You Can’t Ask That in a way. Creating content that dispels myths. It certainly opened our eyes.

Treating Paedophiles Before They Offend, Hungry Beast, 2010

In 2009, media personality and TV producer Andrew Denton had an idea for a new TV show. He wanted to find the hottest new talent in the country and put them in a room together to make a new kind of current affairs show, called Hungry Beast. 1000 people from across the country applied, including me. I entered some Vive Cool City content.

I was one of 10 people hired to work on the show as a reporter. When I was hired, it was with the expectation that I would continue to delve into the taboo, misunderstood and the fringes as I was doing on Vive Cool City.

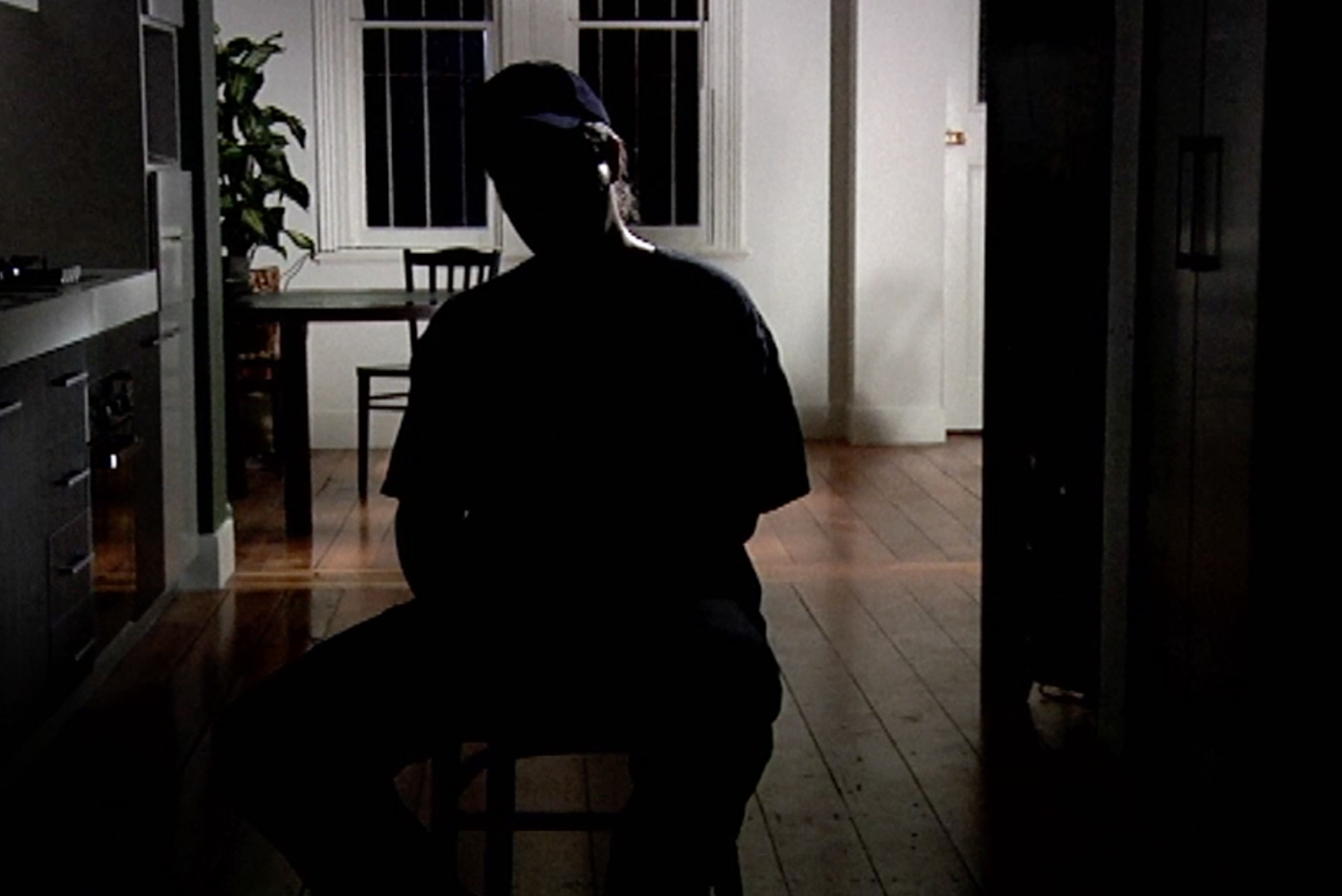

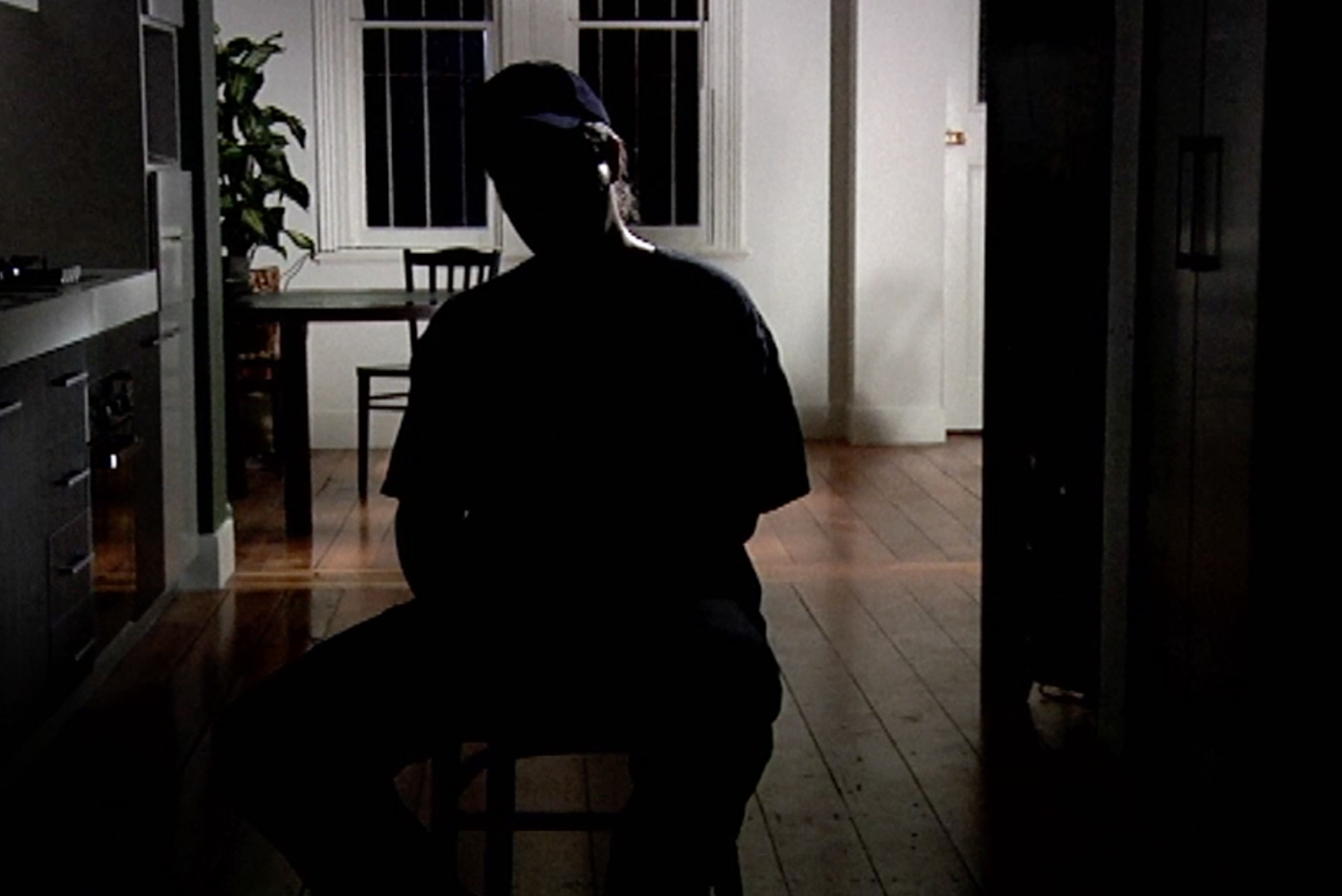

This story came from a simple thought – surely no-one wants to be a paedophile. So what happens to someone as they grow up to become one?

I learnt some valuable information in the early stages of researching this topic. That there are two things – a paedophile and a child sexual offender. A paedophile is not necessarily a child sexual offender (they can have the feelings without acting on them), and a child sexual offender is not necessarily a paedophile (there are other reasons people offend against a child). Of course, a paedophile can also be a child sexual offender.

I thought empathising with someone that had offended against a child would be difficult, so to understand this topic, my aim was to find someone that identified with being a paedophile but hadn’t offended. It took me months, and ultimately through a therapist that worked with people that identified this way, I was put in touch with a client who was willing to tell me his story.

There were quite a few lessons for me in making this piece – but one I’ll highlight. Once I’d finished the interview, my executive producer Andrew Denton asked to see the raw interview. I exported out 20 mins of the best stuff but he instead asked to see the full interview. I was a bit nervous about having my interview pored over by him. After watching it, he had some really valuable feedback for me:

You did a great job, finding this person, and getting them to tell their story. But you could have gone harder – asked harder questions. Your reasons for doing the piece were clear. You did an excellent job preparing him. He came expecting to answer the tough questions, and you owed it to him and the audience to ask the tough questions.

It’s a lesson I think about often. If you do the work, have the courage to ask the tough questions.

WATCH: Treating Paedophiles Before They Offend PASSWORD: TheOutside

*One other note, for the safety of the interviewee, we obscured his identity.

Treating Paedophiles Before They Offend, Hungry Beast, 2010

In 2009, media personality and TV producer Andrew Denton had an idea for a new TV show. He wanted to find the hottest new talent in the country and put them in a room together to make a new kind of current affairs show, called Hungry Beast. 1000 people from across the country applied, including me. I entered some Vive Cool City content.

I was one of 10 people hired to work on the show as a reporter. When I was hired, it was with the expectation that I would continue to delve into the taboo, misunderstood and the fringes as I was doing on Vive Cool City.

This story came from a simple thought – surely no-one wants to be a paedophile. So what happens to someone as they grow up to become one?

I learnt some valuable information in the early stages of researching this topic. That there are two things – a paedophile and a child sexual offender. A paedophile is not necessarily a child sexual offender (they can have the feelings without acting on them), and a child sexual offender is not necessarily a paedophile (there are other reasons people offend against a child). Of course, a paedophile can also be a child sexual offender.

I thought empathising with someone that had offended against a child would be difficult, so to understand this topic, my aim was to find someone that identified with being a paedophile but hadn’t offended. It took me months, and ultimately through a therapist that worked with people that identified this way, I was put in touch with a client who was willing to tell me his story.

There were quite a few lessons for me in making this piece – but one I’ll highlight. Once I’d finished the interview, my executive producer Andrew Denton asked to see the raw interview. I exported out 20 mins of the best stuff but he instead asked to see the full interview. I was a bit nervous about having my interview pored over by him. After watching it, he had some really valuable feedback for me:

You did a great job, finding this person, and getting them to tell their story. But you could have gone harder – asked harder questions. Your reasons for doing the piece were clear. You did an excellent job preparing him. He came expecting to answer the tough questions, and you owed it to him and the audience to ask the tough questions.

It’s a lesson I think about often. If you do the work, have the courage to ask the tough questions.

WATCH: Treating Paedophiles Before They Offend PASSWORD: TheOutside

*One other note, for the safety of the interviewee, we obscured his identity.

Demolition Man, 2015

My aim was always to get my own show commissioned. We had a pilot of Vive Cool City commissioned for a major network, but commissioning editors changed and that project was put on the back burner. Other ideas were fleshed out and run by networks but never got up. I worked on other programs, one being an Australian version of a US blokey reality format called American Pickers – where 2 blokes would go around to mainly old men’s properties looking for collectables, furniture, memorabilia, old cars etc, that they would identify and try and buy for a good price, and sell on. I thought it wasn’t the sort of show I wanted to work on, but I needed the money! When I came to make the show, I realised there were some similarities to the sort of content I liked to make – mainly weird characters that were into fringe culture. I learnt valuable lessons on content making by doing two seasons of this show.

One extra bonus was meeting a character on a shoot one day that I thought could be his own program.

The issue, as I saw it with Aussie Pickers, was that it was not authentic – it was trying to make Australians do this American thing. It worked as TV but it didn’t feel real to me. I wanted to see an Aussie version of this sort of show.

The character I met was one of the most Australian people I had ever met. A demolisher named Lawrie. From this moment, I worked up a pitch for a show called Demolition Man, where we followed Lawrie and his gang around as they demolished houses and found treasures.

The show was picked up for 10 episodes and has also appeared on a number of networks around the world.

By this point in time in my career I had interviewed thousands of people, but Lawrie was a unique challenge of his own. For one, despite being very good on camera, he had almost no interest in being filmed. Every time we stopped him for a short interview he would be pissed off. We’d arrive at a shoot and before we had a chance to get the cameras out, he’d be hacking away treasures from the house with his pick while we missed the shot. This was a 12-week shoot mind you, so I had to sort it out somehow.

What I realised was I needed to understand why he had decided to accept being filmed. What did he want out of it? Eventually, I learnt that he didn’t want to be portrayed as a doofus or an opportunist out for a quick cash-grab (which is often how these shows simplify their protagonists). He wanted the audience to see his true personality and he didn’t want to be told how to behave. Once I worked this out and let him know that we shared the same goal, things started to go a lot smoother. Ultimately it took a lot of gentle manoeuvring, resilience and good timing to get the interviews plus I had to work out how to speak his language without “putting it on” – Lawrie had no time for bullshitters. I also figured out how to film without getting in the way of his work, which made life easier for both of us.

WATCH: Demolition Man

Demolition Man, 2015

My aim was always to get my own show commissioned. We had a pilot of Vive Cool City commissioned for a major network, but commissioning editors changed and that project was put on the back burner. Other ideas were fleshed out and run by networks but never got up. I worked on other programs, one being an Australian version of a US blokey reality format called American Pickers – where 2 blokes would go around to mainly old men’s properties looking for collectables, furniture, memorabilia, old cars etc, that they would identify and try and buy for a good price, and sell on. I thought it wasn’t the sort of show I wanted to work on, but I needed the money! When I came to make the show, I realised there were some similarities to the sort of content I liked to make – mainly weird characters that were into fringe culture. I learnt valuable lessons on content making by doing two seasons of this show.

One extra bonus was meeting a character on a shoot one day that I thought could be his own program.

The issue, as I saw it with Aussie Pickers, was that it was not authentic – it was trying to make Australians do this American thing. It worked as TV but it didn’t feel real to me. I wanted to see an Aussie version of this sort of show.

The character I met was one of the most Australian people I had ever met. A demolisher named Lawrie. From this moment, I worked up a pitch for a show called Demolition Man, where we followed Lawrie and his gang around as they demolished houses and found treasures.

The show was picked up for 10 episodes and has also appeared on a number of networks around the world.

By this point in time in my career I had interviewed thousands of people, but Lawrie was a unique challenge of his own. For one, despite being very good on camera, he had almost no interest in being filmed. Every time we stopped him for a short interview he would be pissed off. We’d arrive at a shoot and before we had a chance to get the cameras out, he’d be hacking away treasures from the house with his pick while we missed the shot. This was a 12-week shoot mind you, so I had to sort it out somehow.

What I realised was I needed to understand why he had decided to accept being filmed. What did he want out of it? Eventually, I learnt that he didn’t want to be portrayed as a doofus or an opportunist out for a quick cash-grab (which is often how these shows simplify their protagonists). He wanted the audience to see his true personality and he didn’t want to be told how to behave. Once I worked this out and let him know that we shared the same goal, things started to go a lot smoother. Ultimately it took a lot of gentle manoeuvring, resilience and good timing to get the interviews plus I had to work out how to speak his language without “putting it on” – Lawrie had no time for bullshitters. I also figured out how to film without getting in the way of his work, which made life easier for both of us.

WATCH: Demolition Man

The Age of Innocence, Hello Stranger episode 3, 2015

At the same time I was making Demolition Man, I was also pitching a new show based on a weekly three-minute vox pop segment I did on Hungry Beast. This segment broke from the tradition of the typical “news of the day” street vox pop. I was more interested in asking the people I met in the street questions about life – big universal questions that anyone could answer based on their own lives and experiences. I would then edit the answers together to form a larger story. The editing style of You Can’t Ask That originated here (the editor of these would go on to edit YCAT). The premise of these pieces was to understand the humanity of the person walking past you in the street – to find out if we are really so different from each other.

I interviewed hundreds of people this way, and time and again they would tell me the most interesting, personal, unfiltered details of their lives. Often incredible stuff never made the edit. We felt there was a program in going deeper into some of these people’s lives.

The idea of Hello Stranger was to paint a modern snapshot of Australia – different from the lifesaver, jackaroo image that was typical but out of date. I would travel the country, interviewing people I met in the street, and then if I came across someone interesting, I would follow them home and tell their story. Each episode starts with a vox pop, before going into a feature piece on an Aussie we met.

This episode began with the question, When did you lose your innocence? A question that inspired a myriad of personal, emotional responses. We then dipped into the life of Lorraine Dooley, a debutante ball instructor in the final days leading into the big night. She initially came across as a hard-arse footy coach type, but behind that tough exterior was someone, like many of us, working hard to keep it all together.

WATCH: Hello Stranger, The Age Of Innocence

This show was hard work. Interviewing people in the street takes a lot of energy. But I was blown away time and again by how quickly they would open up if I listened and gave a shit. It is also my favourite way to interview. Having a couple of big questions as a launching place, but then the rest is up to me to listen and follow my instincts. No big sheet of questions, just my own curiosity. I interviewed 500 people in the street across this series.

The Age of Innocence, Hello Stranger episode 3, 2015

At the same time I was making Demolition Man, I was also pitching a new show based on a weekly three-minute vox pop segment I did on Hungry Beast. This segment broke from the tradition of the typical “news of the day” street vox pop. I was more interested in asking the people I met in the street questions about life – big universal questions that anyone could answer based on their own lives and experiences. I would then edit the answers together to form a larger story. The editing style of You Can’t Ask That originated here (the editor of these would go on to edit YCAT). The premise of these pieces was to understand the humanity of the person walking past you in the street – to find out if we are really so different from each other.

I interviewed hundreds of people this way, and time and again they would tell me the most interesting, personal, unfiltered details of their lives. Often incredible stuff never made the edit. We felt there was a program in going deeper into some of these people’s lives.

The idea of Hello Stranger was to paint a modern snapshot of Australia – different from the lifesaver, jackaroo image that was typical but out of date. I would travel the country, interviewing people I met in the street, and then if I came across someone interesting, I would follow them home and tell their story. Each episode starts with a vox pop, before going into a feature piece on an Aussie we met.

This episode began with the question, When did you lose your innocence? A question that inspired a myriad of personal, emotional responses. We then dipped into the life of Lorraine Dooley, a debutante ball instructor in the final days leading into the big night. She initially came across as a hard-arse footy coach type, but behind that tough exterior was someone, like many of us, working hard to keep it all together.

WATCH: Hello Stranger, The Age Of Innocence

This show was hard work. Interviewing people in the street takes a lot of energy. But I was blown away time and again by how quickly they would open up if I listened and gave a shit. It is also my favourite way to interview. Having a couple of big questions as a launching place, but then the rest is up to me to listen and follow my instincts. No big sheet of questions, just my own curiosity. I interviewed 500 people in the street across this series.

Suicide Attempt Survivors, You Can’t Ask That season 2 ep 3, 2017

We actually pitched You Can’t Ask That at the same time as Hello Stranger. They were commissioned simultaneously, so we made both shows at the same time with the same team. One day I’d be vox-popping in the street, the next I’d be shooting interviews in-studio for You Can’t Ask That.

Out of the two ideas, You Can’t Ask That was the more unknown. We sort of knew what Hello Stranger would look like, based on our prior work. You Can’t Ask That was a combination of the vox pops and stories I’d been making up until then, looking to understand misunderstood, taboo or fringe culture. The show was also a response to the “political correct” conversation that was happening at the time. Everyone suddenly became very afraid of saying the wrong thing or insulting someone. They became obsessed with terminology and correcting anyone that got it wrong rather than having thoughtful and respectful conversations. The idea of procuring the questions from the audience anonymously was so that people could ask those questions they wanted to know, but felt afraid to. The show was about stereotype-busting and understanding people, but also giving insights into unknown worlds. About normalising real conversations – the sorts of conversations I’d been having for years.

The episode on Suicide Attempt Survivors was one I was particularly keen on making. Like many, I have known people in my life that have self-harmed, attempted to take their life and died from suicide. Around the time of making this episode, I watched as a number of friends grappled with close ones being at risk of suicide or dying from suicide. What dawned on me was that it didn’t matter how educated you were, whether you’re rich or poor, everyone was being impacted by mental health and most people don’t have the tools to deal with these big conversations when they’re happening to loved ones. In particular, suicide is not talked about. In private conversations or in the media.

In terms of the media, there was a reason for it. There is deep fear that if suicide is spoken about it will cause a domino effect. There is no evidence however that this is the truth. In fact, I believe the opposite is true. Speaking about these issues normalises them – it makes them ok to speak about, it helps talk about it constructively and it shows we are not alone in our feelings or experiences when it comes to something like suicide.

To get this episode to air, we partnered with SANE Australia. We also approached the psychiatrist and then Australian Of The Year, Patrick McGorry, who not only watched the piece and endorsed it, but did so in a spoken piece to camera at the beginning of the episode. The episode caused a huge reaction, but not in a negative way. Hundreds of people came out and publicly stated that they too had struggled with suicide or suicidal thoughts and didn’t know how to talk about it or articulate how they felt. This episode helped show them how to do so.

To help me prepare my questions, I worked with a psychologist and psychiatrist in the lead up to the interviews. Our participants were all cleared as mentally stable to speak about their experiences by the show psychologist. After their interviews they were debriefed. Finally, they were all shown the episode before it went to air. All that being said, these were a particularly sensitive series of interviews, where the participants were not “fixed”, so I had to be switched on. But, as you will see in the piece, they appreciated the chance to explain how challenging their lives were. You’ll also see a side of suicide that you have never seen before.

Suicide Attempt Survivors, You Can’t Ask That season 2 ep 3, 2017

We actually pitched You Can’t Ask That at the same time as Hello Stranger. They were commissioned simultaneously, so we made both shows at the same time with the same team. One day I’d be vox-popping in the street, the next I’d be shooting interviews in-studio for You Can’t Ask That.

Out of the two ideas, You Can’t Ask That was the more unknown. We sort of knew what Hello Stranger would look like, based on our prior work. You Can’t Ask That was a combination of the vox pops and stories I’d been making up until then, looking to understand misunderstood, taboo or fringe culture. The show was also a response to the “political correct” conversation that was happening at the time. Everyone suddenly became very afraid of saying the wrong thing or insulting someone. They became obsessed with terminology and correcting anyone that got it wrong rather than having thoughtful and respectful conversations. The idea of procuring the questions from the audience anonymously was so that people could ask those questions they wanted to know, but felt afraid to. The show was about stereotype-busting and understanding people, but also giving insights into unknown worlds. About normalising real conversations – the sorts of conversations I’d been having for years.

The episode on Suicide Attempt Survivors was one I was particularly keen on making. Like many, I have known people in my life that have self-harmed, attempted to take their life and died from suicide. Around the time of making this episode, I watched as a number of friends grappled with close ones being at risk of suicide or dying from suicide. What dawned on me was that it didn’t matter how educated you were, whether you’re rich or poor, everyone was being impacted by mental health and most people don’t have the tools to deal with these big conversations when they’re happening to loved ones. In particular, suicide is not talked about. In private conversations or in the media.

In terms of the media, there was a reason for it. There is deep fear that if suicide is spoken about it will cause a domino effect. There is no evidence however that this is the truth. In fact, I believe the opposite is true. Speaking about these issues normalises them – it makes them ok to speak about, it helps talk about it constructively and it shows we are not alone in our feelings or experiences when it comes to something like suicide.

To get this episode to air, we partnered with SANE Australia. We also approached the psychiatrist and then Australian Of The Year, Patrick McGorry, who not only watched the piece and endorsed it, but did so in a spoken piece to camera at the beginning of the episode. The episode caused a huge reaction, but not in a negative way. Hundreds of people came out and publicly stated that they too had struggled with suicide or suicidal thoughts and didn’t know how to talk about it or articulate how they felt. This episode helped show them how to do so.

To help me prepare my questions, I worked with a psychologist and psychiatrist in the lead up to the interviews. Our participants were all cleared as mentally stable to speak about their experiences by the show psychologist. After their interviews they were debriefed. Finally, they were all shown the episode before it went to air. All that being said, these were a particularly sensitive series of interviews, where the participants were not “fixed”, so I had to be switched on. But, as you will see in the piece, they appreciated the chance to explain how challenging their lives were. You’ll also see a side of suicide that you have never seen before.

I have a monthly newsletter called Questionable Advice where I write about what I’ve learnt interviewing 1000s of people. Sign up here if you’d like to receive it.

Most up-to-date information about me can be found at kirkdocker.com